Performance

Athletes from the casual pick-up soccer player to the Olympic decathlete need to perform optimally and without injury. Simulation can reveal how muscles orchestrate motions like jumping, sprinting, kicking, and cycling. This information is vital for identifying patterns that maximize performance or would lead to a muscle sprain or joint overload.

Hit the Ground Running: Revealing muscle contributions to propulsion and support during running.

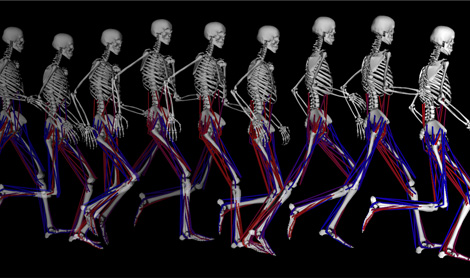

Track athletes circling the Olympic oval make running appear effortless, but runners use a complex orchestration of muscles to propel their body forward at each stride. Samuel Hamner of Stanford University is spearheading a project using OpenSim to understand which muscles are responsible for supporting the body and accelerating it forward during running. Hamner created a three-dimensional model of the body and used OpenSim to generate a simulation of running driven by 92 different muscles.

Hamner and his project team demonstrated that two muscle groups are the major players in running. When a runner’s foot first hits the ground, known as the braking phase, the body responds to the impact of the foot strike by using the quadriceps (the large muscles in the front of the thigh) to brake the body’s forward motion, and also support the body by preventing the leg from collapsing. Then, during the propulsive phase, when the runner is preparing for push-off, the plantar flexors (the calf muscles) make the biggest contribution to both supporting the body and propelling it forward.

A muscle actuated simulation of running. Muscles activated at each phase of the running cycle are shown in red.

A muscle actuated simulation of running. Muscles activated at each phase of the running cycle are shown in red.

These initial findings lay the groundwork for further investigation of injury and joint disease. In the future, OpenSim could be used to understand how different muscle forces change how the hip and knee joints are loaded. Do different running patterns increase or decrease joint loads? Unraveling the relationship between running gait muscle forces, and the forces in the hip and knee is essential for revealing the mechanisms of traumatic injuries, like hamstring tears, and degenerative diseases, like osteoarthritis.

To learn more about the model used in the project and the simulations of running, visit Hamner’s project on SimTK.org.